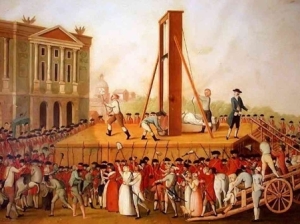

Execution of Marie Antoinette.

by Marque A. Rome

Google News carried a headline from the Lawfare Website, which is associated with the influential Brookings Institution, anent Thailand’s ongoing political catharsis. Entitled ‘More Bangkok Blues: An Update on Thailand’s Political Crisis‘, it was written by Ritika Singh, a graduate in 2011 of New York’s Skidmore College, a sort of Ivy League girls school, currently “project coordinator at the Brookings Institution where she focuses on national security law and policy,” and, though evidently rooted ethnically in the sub-continent, one who calls Bangkok her “hometown.”

From Bangkok, eh? Yet Ritika’s analysis is surprisingly shallow, as shallow as that of any foreign journalist who likes working in Thailand and fears permanent exile should he trample some high institution’s feet. Her views differ significantly from what I see in the Thai-language press.

For example, she conveniently divides Bangkok’s contesting parties into ‘populist’ supporters of Thaksin Shinawatra and his Pheu Thai Party government, and the anti-Thaksin ‘urban classes’. This has been the stuff of Reuters, Associated Press, and Agence France Press since the troubles began, but we should expect something a little more nuanced from an educated and elite scion of Bangkok, whose opinions are underscored by association with the illustrious Brookings Institution, founded in 1916 and America’s preeminent think-tank, situated as it is on Embassy Row in Washington D.C.

Thaksin is supported by the rural poor? No, not all of them; in the south they hate him. He, his parties, politics and associates (including his sisters and wife’s family) are supported almost universally in the north and northeastern provinces. Rich and poor alike are keen on his economic programmes and many among the class that passes for educated in this country believe the future is with him and not with the group that has ruled for as long as anyone alive can remember.

Thaksin has a good deal of support even in Bangkok and the south, though it can be dangerously impolitic to admit that in the wrong company. People on both sides and in the middle realise significant political and social change is impending. Thaksin and his principal supporters are, par excellence, businessmen — not populists — and the underlying issue is who will inherit, the business class or the old guard.

So forget about ‘populism’: that’s just a red herring, not a defining factor.

The mass of protesters on either side are mere pawns, politically unsophisticated and hardly aware of their leaders’ underlying motives. That’s why, far from being ‘violent’, the protest environment is much like a temple fair, with music, dancing, games, and vendors selling refreshments and souvenirs all round. The protests led by Suthep Thaugsuban and the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) are an entertainment extravaganza, literally programmed for TV and broadcast in their entirety on the Democrats’ Blue Sky cable channel.

The idea that popular angst dominates the scene, or even colours it to any great extent, is preposterous.

“Bangkok has been roiled by many months of protests,” Ritika writes, “which shut down the city and remained violent until fairly recently.” This is the merest nonsense. Violence, as a matter of fact, has been so rare most incidents thereof are generally supposed to be staged. Pro-government red shirt leaders openly say so, pointing out that they have nothing to gain from such incidents, which are clearly contrived to excite sympathy among the gullible.

How else can one explain why the bombs and bullets never target PDRC leaders? Never do more than cosmetic damage to their homes and vehicles? 25 persons have been killed in violence that might be associated with the protests, which have involved millions of people, over a period of nearly seven months. Bangkok is a city of 15 million. Though representing real tragedy for those killed and their families, 25 dead is not a statistically significant figure. It is not even clear politics played any part in the deaths of some, because many of the PDRC’s rank and file are low class thugs, drug addicts and ex-cons.

What is clear is that weapons caches so far discovered have been attributed entirely to PDRC people and to military agents suspected of secretly working against the government.

Ritika notes that the city was “shut down”: in a pig’s eye, perhaps, and in the dreams of Suthep, that might have been the case. But the reality was different. The “shut down” movement resulted in increased traffic congestion occasionally at seven points in the city. Otherwise people have gone about their business without hindrance and without fear. The chief complaints have been from taxi drivers and small business owners suffering reduced tourist numbers.

It is an open secret that the mass of protesters, whether from Isan on the red shirt side, or from the south on Suthep’s side, are ferried to Bangkok free, paid, fed and generally taken care of for their trouble.

Some revolution.

With enough prodding, one supposes, it might still erupt into civil war — but it will be a war between personalities, each supported by mercenary thugs, not a war of deeply-held convictions, of classes or regions. It will be a made-for-TV war, a war of those who, like hired mourners at a Chinese funeral, are paid to cry out.

‘Lawfare’, according to the Website’s principals, is a US New Speak term that means ‘warfare by means of law’, and might reasonably be used to describe the strategy used to topple yesterday Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra and nine members of her cabinet. Others call it simply a ‘judicial coup’. Ritika explains in her piece that the case concerned “Prime Minister Yingluck’s alleged abuse of power when she transferred a civil servant to another position three years ago—an issue that nobody really cares about….”

Ritika, Yingluck wasn’t in office three years ago, and Thawil Pliensri was not just another civil servant: he was head of the nation’s Security Council. The prime minister of Thailand has never been challenged on such a transfer before, it being within a prime minister’s prerogative to decide with whom he shall work. It is undoubtedly true that Thawil was transferred as part of a scheme to make Pol Gen Priewpan Damapong head of the National Police Office. In deciding against Yingluck, the court noted that Priewpan is ‘related’ to Yingluck, and called that an abuse of power.

Priewpan is brother of Thaksin’s ex-wife, Potjaman, and thus uncle to Thaksin’s offspring by her. But, strictly speaking, he is no longer legally related to Yingluck. Moreover, the Damapong clan have been powerful within the police since long before Thaksin took office in 2001. Thaksin’s career as lieutenant colonel of police was promoted by Potjaman’s uncle, a police general, and he left the force when that uncle retired. His debut in business was financed from money loaned for the purpose by Potjaman’s family, and the Damapongs also put up money to start Thaksin’s Thai Rak Thai Party, from which the Pheu Thai Party derives.

Parties associated with Thaksin have been paramount in Thailand since 2001, and Priewpan was a leading police officer. His promotion was no more out of the ordinary than Thawil’s transfer — but the Constitution Court affected to see a hidden agenda in what was perfectly plain: that the prime minister wanted a political ally as police chief. That this constitutes an abuse of power gross enough to result in removal not only of the prime minister, but of nine other ministers who voted for Thawil’s transfer, is simply beyond belief.

What happened was plainly a judicial coup, or ‘lawfare’ if you will, just as removals of prime ministers Samak Sundaravej and his successor, Somchai Wongsawat, were in 2008. The court removed Samak for teaching cooking on TV, and Somchai because a member of his party was convicted of vote-buying, and in the latter case the court ordered Somchai’s party dissolved.

Charges against all three — Samak, Somchai, and Yingluck — served as mere pretexts. Their real crimes were in siding with Thaksin, who was removed by military coup from office in 2006, and in being more popular among the electorate than their opponents. But the the last military coup had uncomfortable results, leading to Yingluck’s election with a comfortable majority in 2011, and so the opponents of ‘Thaksinism’ focused on the courts as a new way to attack their nemesis.

If readers have any lingering doubt that Yingluck is victim of political gang rape, consider that yesterday the Office of the Auditor General decided to dun her 3.8 billion baht, the cost of the 2nd February elections, also nullified by the court. The OAG’s thinking is that, even though elections are mandated under the constitution within 60 days after parliament’s dissolution, and even though no clear constitutional mechanism exists for delaying such elections, Yingluck should have known the political atmosphere was too charged to admit of elections, should have ignored the majority’s desire to settle matters with a vote, and illegally cancelled the elections.

Because she didn’t, she alone must pay. The OAG might just as reasonably charge the Election Commission for organising the elections, the candidates for campaigning, or voters for going to the polls, but didn’t. They are not the target, Yingluck is; so she gets the bill.

The great question is, “What happens next?” Though, contrary to Ritika’s assertion, protests in Bangkok have been mostly peaceful, awareness is growing among the masses as to who is really behind the protests and what the real agenda is. Neither the Thai press nor protest leaders on either side make much of the ‘urban rich’/ ‘rural poor’ divide that is the focus of foreign language news agencies. The issues in Thailand today, believe it or not, do not differ greatly from the issues in France that led to the storming of the Bastille and republican government.

Demand is growing among all classes for elimination of privilege, for a neutral judiciary, honest constabulary and civil service, transparency in government, and democracy unsullied by ‘dark influences’. Hitherto the great mass of the Thais has been apolitical. But Suthep’s crusade and accompanying incidents are politicizing even housewives. Somewhere over the horizon a convulsion looms. How far distant and how violent can only be conjectured, but surely it will have little relation to circumstances outlined by Ritika in her Lawfare piece — and there’s the rub.

Normally it matters little what pundits posit, but Lawfare’s connection to the Brookings Institution puts matters in different perspective, because the Brookings is a principal component of the US Establishment. Its analyses tend to be among those on which the government acts. So if the US government thinks troubles in Thailand are based on conflict between ‘urban rich’ and ‘rural poor’, policy makers there will be blind-sided by what really is happening, just as they were by the Arab Spring and by ethnic Russian reaction to the Ukraine coup earlier this year — and when the US government makes mistakes in policy based on misunderstanding of circumstances, results tend to be bloody and prolonged.

Think ‘Vietnam’, then pray for Thailand.